It Works Here

Reclaiming the 15-Minute DNA of the American Small Town in Iowa, Indiana, and New Hampshire

When building statewide coalitions in the U.S., a common critique of bike, pedestrian, and transit investment is that it “won’t work for rural areas.” The assumption behind this claim is that rural life is defined by long-distance travel between far‑flung towns and cities. Most rural trips, like most urban trips, are short, local, and predictable. The problem is not geography. It is that we design policy and infrastructure as if the longest possible trip is the only one that matters.

This critique collapses two very different types of travel into one. Intertown travel, commutes of ten, twenty, or even fifty miles, will continue to rely on cars for the foreseeable future. No serious advocate is arguing otherwise. But intratown travel, the daily trips to the general store, library, post office, school, or town hall, is where walking and biking make the most sense, especially in rural towns whose physical form was built around exactly those kinds of trips.

West Lafayette, Indiana

Across the country, but especially in the Northeast and Midwest, rural towns are not sprawling landscapes; they are compact, walkable places. Many residents live within towns that are only a few miles across from end to end. If you zoom in on a map of a typical New Hampshire railroad town or a Midwestern agricultural hub, you stop seeing the sprawl that defines the outskirts of Boston or Chicago. Instead, you see a geometry that urban planners in large cities are desperate to recreate: tight street grids, frequent intersections, and services clustered around a historic center. The bones of a 15‑minute city are in Keene and Marshalltown, not New York and Los Angeles. We just stopped seeing them that way.

The most common objection I hear in rural advocacy spaces is the long commute along state highways. I once commuted from my hometown of Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire, to Concord, a 54‑mile trip. I met someone who regularly biked that distance. Even as a cycling advocate, I would never do it myself or recommend it to anyone. Opponents of bike and pedestrian investment point to commutes like this as if they are typical. They are not. Most trips people take are far shorter. We are not trying to replace a 50‑mile commute with a bike ride. We are trying to replace the two‑mile trip to the farmers market, the library, or the post office.

Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire

I regularly walk or cycle to Fitzwilliam’s Town Common to attend the farmers' market or visit the town hall. The goal of good infrastructure is not to force everyone to bike, but to make it safe and convenient for people who live nearby to walk or ride, while those who live farther out can still drive. In fact, building bike and pedestrian infrastructure often makes driving easier. Fewer short car trips mean less congestion, fewer turning conflicts, and quieter streets for everyone.

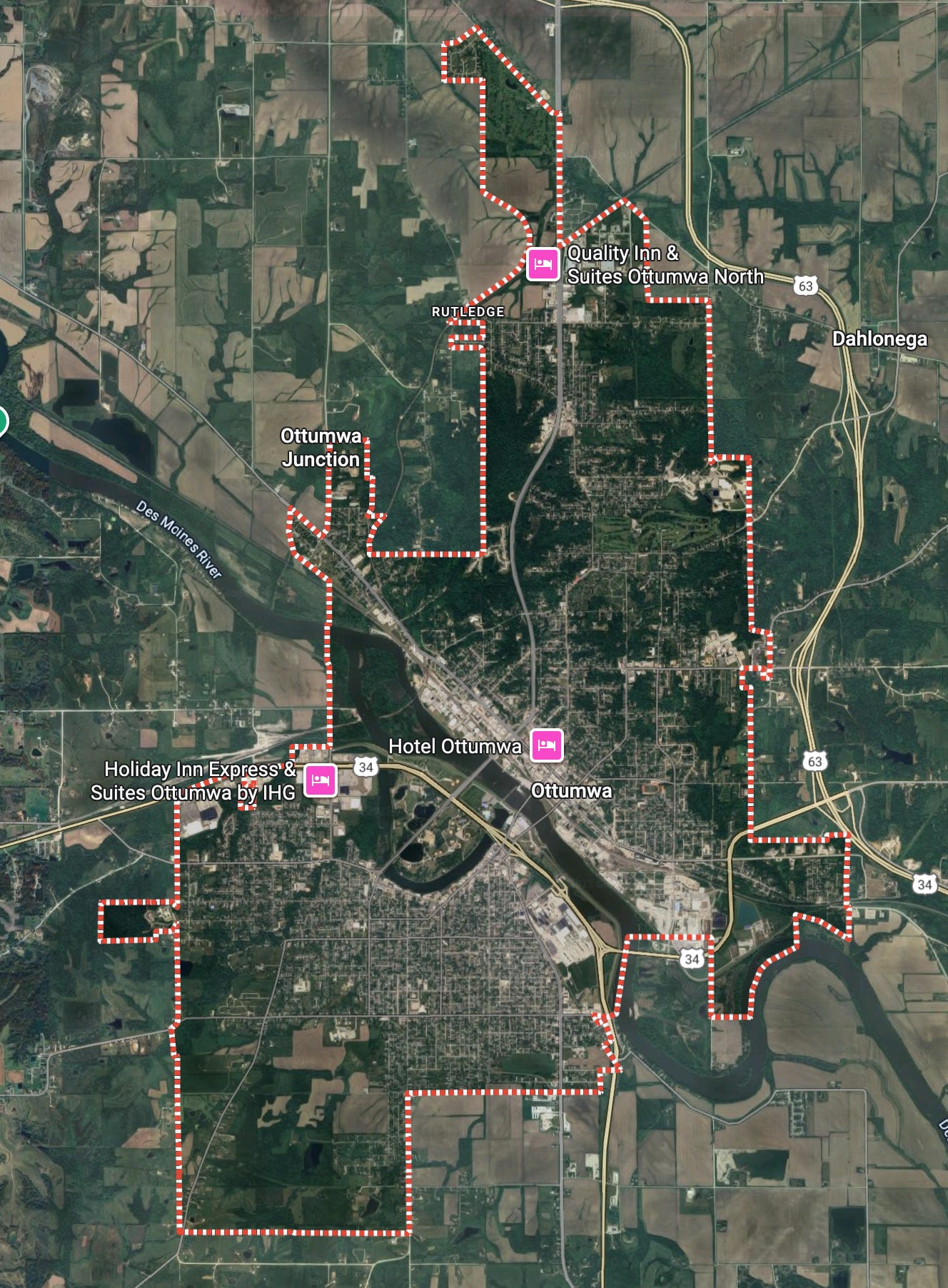

Many towns across Iowa tell the same story. Take Ottumwa: a city built around the railroad so residents could easily reach local jobs and services. Almost no one lives beyond three miles from downtown. From an overhead view, Ottumwa resembles a single neighborhood in a larger city. Intersection density, block length, and service proximity are strikingly similar to what planners celebrate in urban communities. The difference is not form, but context. Cities like Ottumwa stand alone, while similar neighborhoods are embedded within larger metropolitan areas. We have “urban” density; we just surrounded it with cornfields and nature instead of other neighborhoods and suburbs.

Beyond the physical geometry of our towns, we must confront who our current design is actually for. Right now, most rural infrastructure is built exclusively for the narrow window of life between the ages of 16 and 65, those with a valid driver’s license and the financial means to maintain a vehicle. This 'car-only' mandate effectively strands our seniors who wish to age in place with dignity and isolates our teenagers who lack independence. From an economic standpoint, this is a recipe for stagnation. When we fail to provide the vibrant, walkable environments that young adults increasingly crave, we essentially hand them a map out of town. Investing in bike and pedestrian connectivity isn't just about safety; it is a talent retention strategy. If we want the next generation to build their lives and businesses here, we have to stop designing towns that they feel they have to outgrow.

Many of these cities, including Cedar Falls, Iowa, close off their Main Street to cars, allowing only pedestrians for one night each week to encourage people to come downtown and support local businesses. This is also an approach taken in neighborhoods, including my own in Shadyside (Pittsburgh), where the city hosts a series of arts nights, closing Walnut Street, and allowing local artists and artisans to put up shop. Events like these are small investments in the community that encourage people to stay in their hometown, making returns on investments in public schools and youth services.

Cedar Falls, Iowa, Andrew Nawn

We have to reframe conversations about safe transportation from highways to Main Streets. In my Vision Zero advocacy work in New Hampshire, rural road safety conversations often focus almost exclusively on highway speeds and drunk driving. Those issues matter, but they dominate the conversation because state transportation agencies continue to apply highway logic to town centers. Pedestrian safety on Main Street is ignored because we assume pedestrians should not be there. Design standards reinforce that assumption, turning what should be civic spaces into high‑speed corridors.

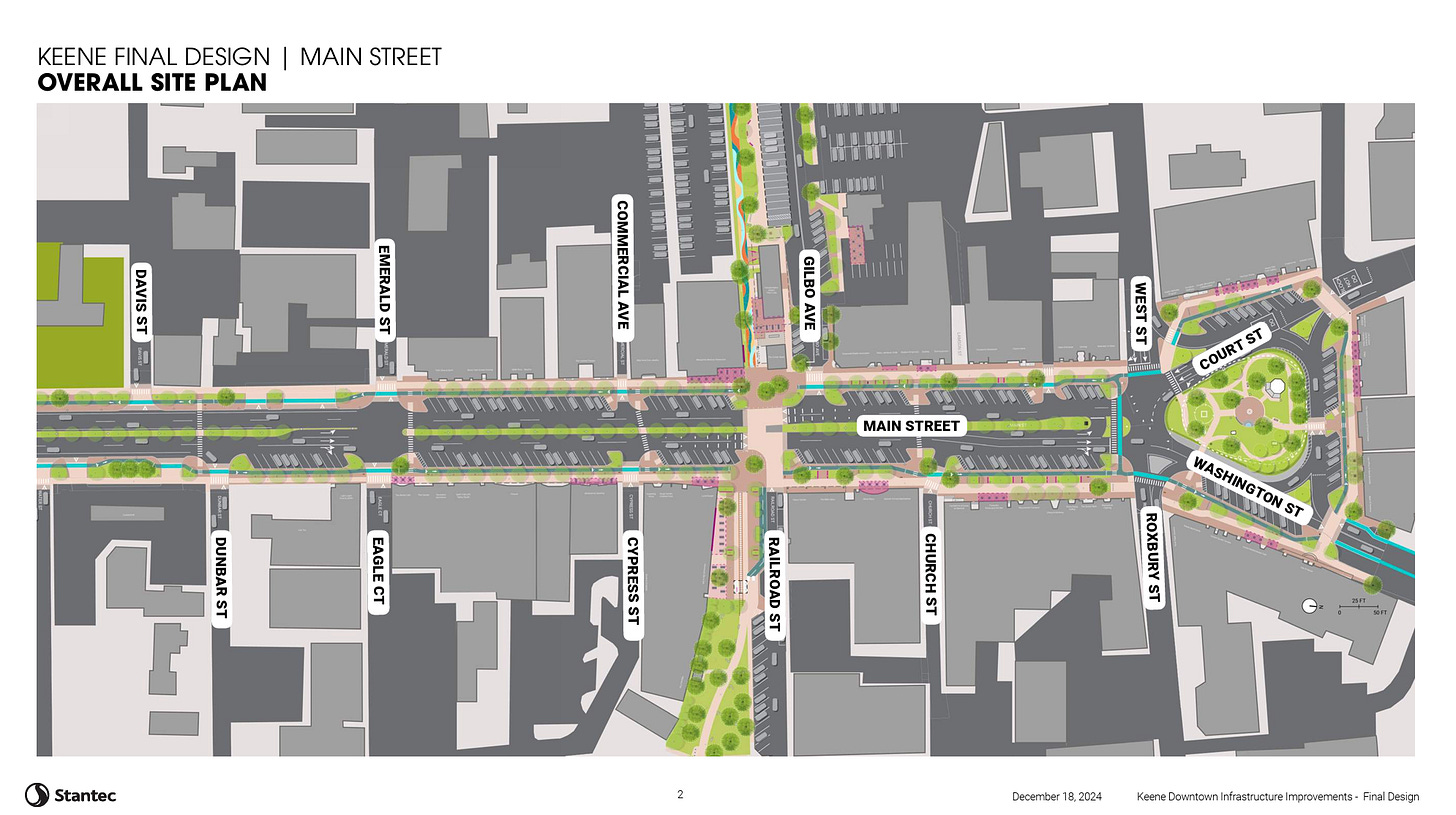

Thankfully, change is possible and already happening. Keene, New Hampshire, is beginning construction on its Downtown Infrastructure Project, reallocating street space to sidewalks and bike lanes while still maintaining parking. West Lafayette, Indiana, offers another example. During a trip to Purdue University with the Pitt Cycling Club, I saw how the university’s integration into the city shifts priorities toward pedestrian safety. State Street, the main east‑west corridor, features concrete‑protected bike lanes, and the riverside road network relies on roundabouts to slow traffic and reduce crashes.

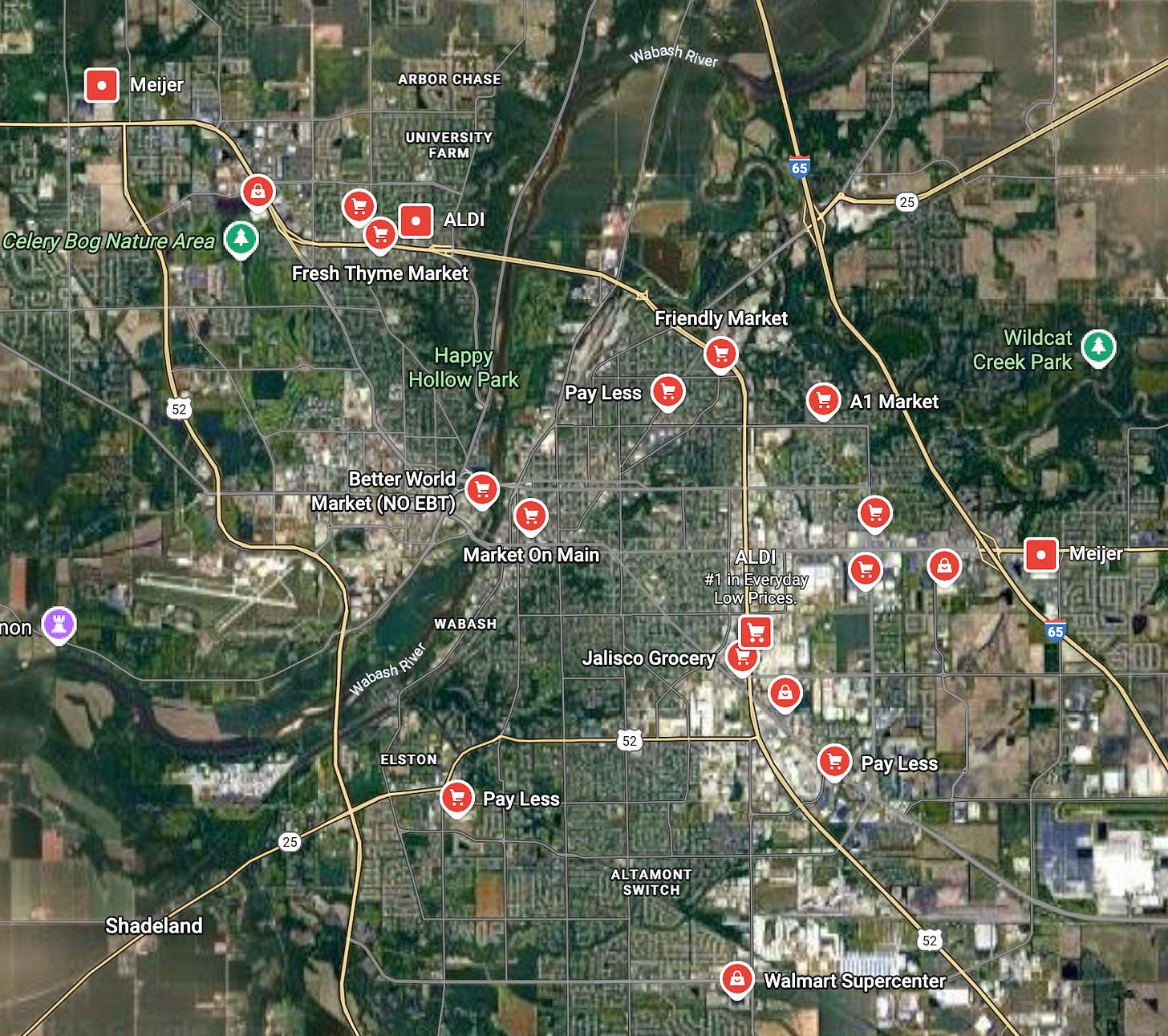

Just across the river, Lafayette, Indiana, tells a familiar story. Its inner neighborhoods share the same bones of good urban design as West Lafayette. However, the most significant hurdle to rural mobility often lies at the edge of town: the ‘stroad.’ While our historic centers have the bones of walkability, our modern essentials, grocery stores, medical clinics, and hardware shops, have often migrated to high-speed corridors like the outskirts of Lafayette. These stretches are designed as highways but function as streets, creating a ‘moat’ around the town center that effectively bars anyone without a car from accessing basic needs.

Grocery stores mapped in Lafayette & West Lafayette

Framing these areas as insurmountable is a mistake; instead, we must view them as the critical missing links. By implementing ‘road diets’ and protected pathways that connect the historic grid to these commercial hubs, we stop treating our towns as two separate worlds and start treating them as a single, functional ecosystem where a trip to the supermarket doesn’t require a two-ton vehicle.

The contrast is not about rural versus urban, it is about political will and design standards. West Lafayette shows what is possible for rural and small‑city communities when streets are treated as places, not highways.

West Lafayette kept developing in the way that the city started, a place for people to get around after getting off the train from Chicago, a place where you don’t need a car. Lafayette, however, changed course when developing the edge of town, adopting 1960s trends and excluding anyone who does not or cannot drive. Many of these downtown areas, like Ames, Iowa, have similarly dense housing and commercial districts, as you may see in many cities’ outer neighborhoods, continuing the legacy that began each city's development. Now, these cities are returning priority to pedestrians in these spaces, adding daylighting and curb bump-outs at crossings, which are rarely seen in many US cities.

Ames, Iowa, Andrew Nawn

Ultimately, the argument that walkability ‘won’t work here’ is a rejection of our own history. Our rural towns were not initially built as thoroughfares for through traffic; they were built for people. They grew around the human scale of a general store, a post office, and a railroad station, all within a short walk or a five-minute ride. That DNA is still there, buried under decades of highway-first engineering.

Uncovering it doesn’t require us to reinvent rural life or mimic the sprawl of a major metropolis. It simply requires the political will to bridge the ‘moats’ we’ve built and design for the trips our neighbors actually take every day. By reclaiming our town centers and connecting them safely to the modern essentials on the edge of town, we aren’t just building bike lanes. We are building a community where a teenager can find independence, a senior can age with dignity, and a new generation can finally see a future worth staying for.